by Fiana Gantheret

International Justice faces challenges that need to be addressed

On 21st November 2016, the WAYAMO Foundation organized a panel discussion to celebrate the one-year anniversary of its Africa Group for Justice and Accountability (AGJA) : Through the Looking Glass – Imagining the Future of International Justice. This discussion, organized as a side-event to the Assembly of States Parties to the Rome Statute (ASP), sought to explore the future of global accountability in the light of the recent declaration of withdrawals of South Africa, Burundi and Gambia from the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. More particularly, and through a preview of Weights and Measures : Portraits of Justice, by American artist Bradley McCallum, it explored the question of opening a dialogue on the challenges faced by international criminal justice.

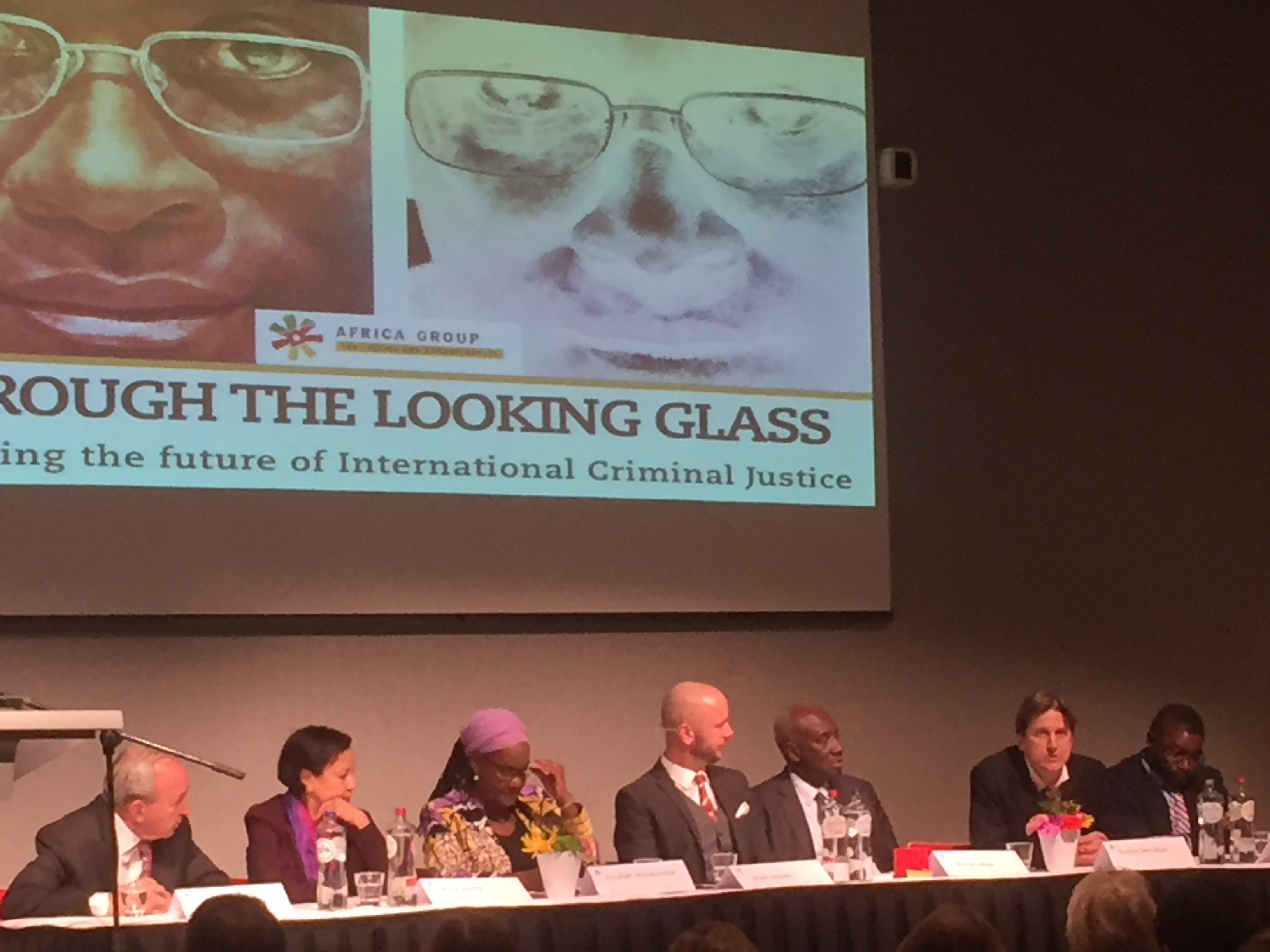

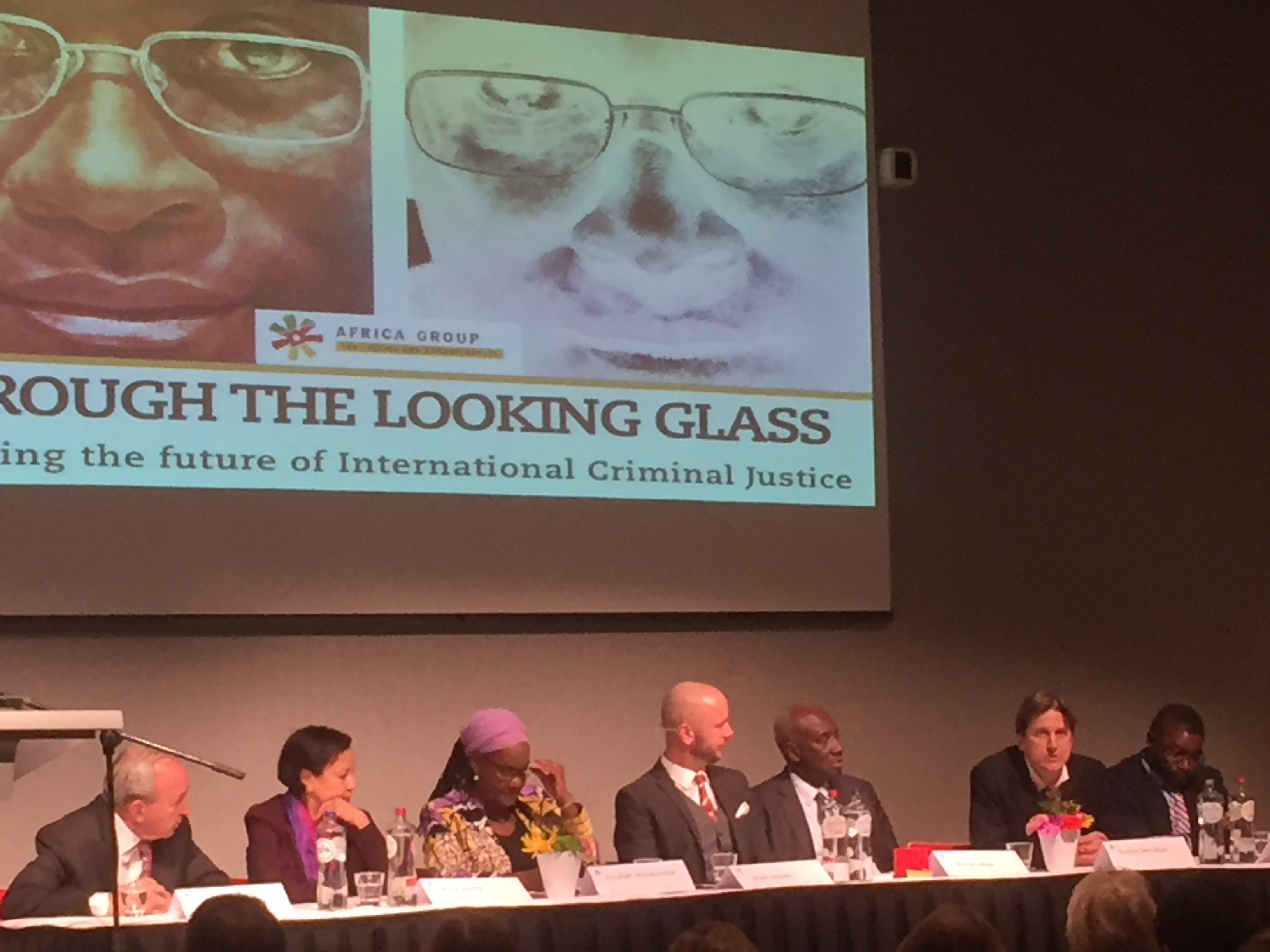

Members of the AGJA participating to the panel were Dapo Akande (Nigeria), Richard Goldstone (South Africa), Hassan Jallow (The Gambia), Athaliah Molokomme (Botswana) and Fatiha Serour (Algeria). The discussion was moderated by WAYAMO’s Research Director Mark Kersten. These prominent members tackled in a compelling way the difficult question of how a global system of international justice, while contemplating its achievements, will face and discuss challenges and, if necessary, renew itself.

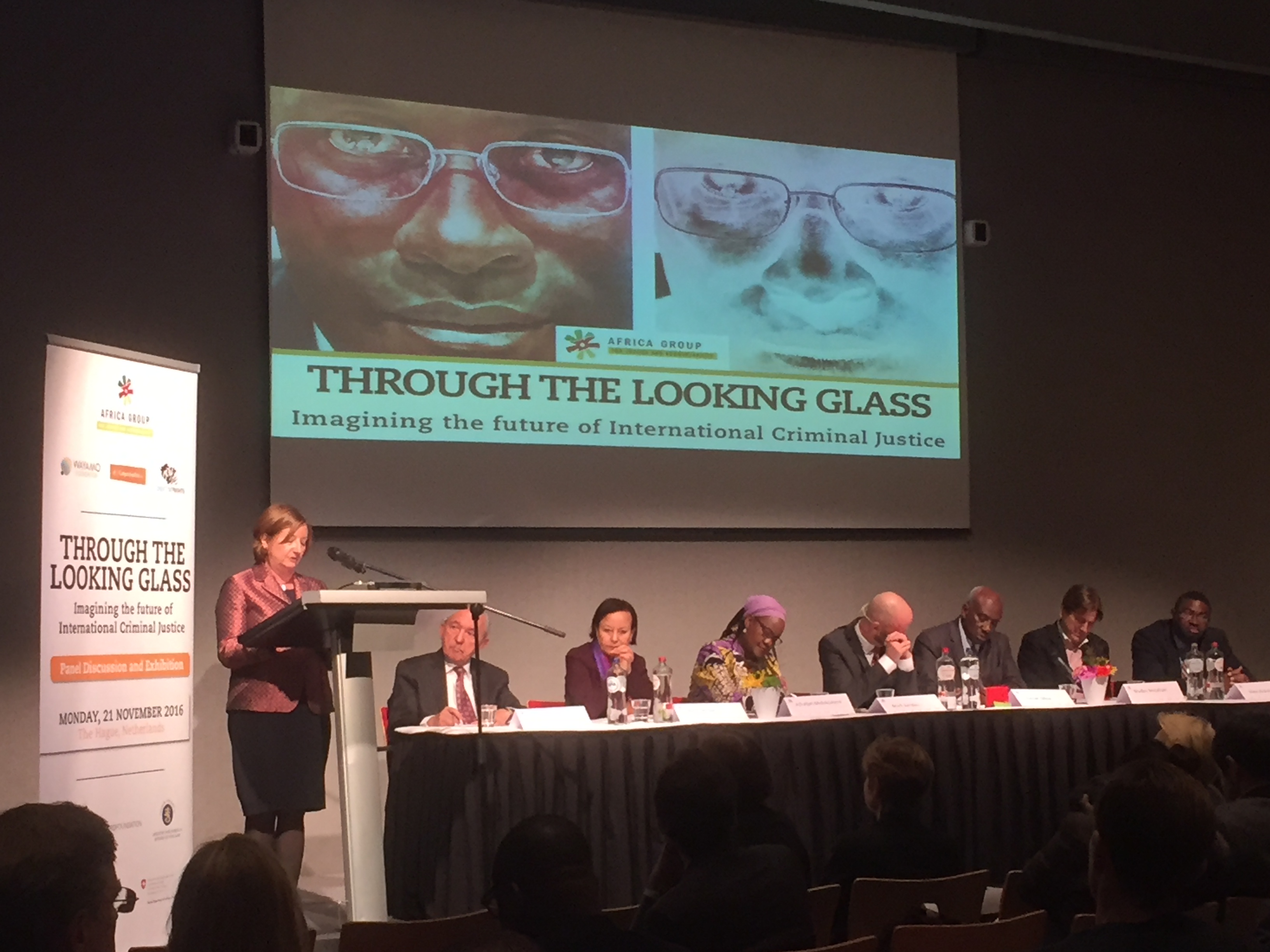

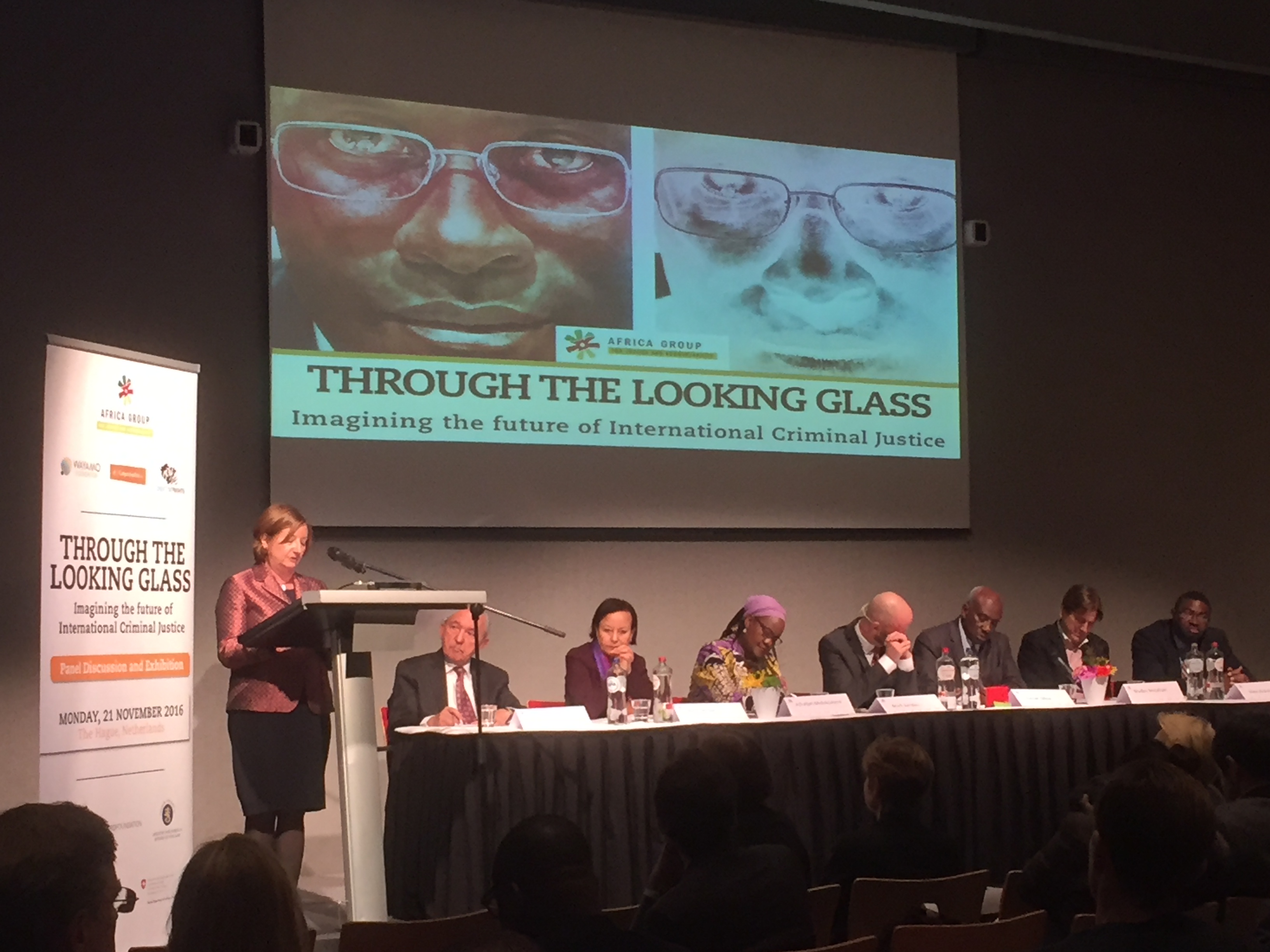

Following introductory remarks by Bettina Ambach, Director of the WAYAMO Foundation, the President of the ICC Silvia Fernandez de Gurmendi reaffirmed that addressing the current difficulties faced by the ICC must be taken seriously and done in an appropriate manner. She put international criminal justice in an historical perspective, recalling that it was a long-term project, requiring efforts to preserve accomplishments and to move forward. Professor Dapo Akande also interestingly placed the discussion on a historical level, emphasising on the fact that this particular moment in time – seeing countries leaving the global justice system they helped to build, as recalled by Richard Goldstone – is part of a process going in the « right direction ». As stated by Hassan Jallow, this process encompasses various elements, such as international tribunals, domestic jurisdictions, and regional mechanisms, each possessing their advantages and disadvantages. President de Gurmendy had also recalled that the role of the Rome Statute goes beyond the reach of the ICC, referring to the definition of crimes in national bodies of law. In that sense, a global justice system is designed to encompass not only international institutions, but also regional and domestic jurisdictions : a « mutually reinforcing global justice system ».

Fatiha Serour emphasized on necessary elements that must be present when setting up a dialogue : respect, trust, and mutual understanding. With these ensured, addressing concerns and working towards identifying common core values can take place. The common core principle, or goal, is stated in Security Council Resolutions 827 and 955, founding the ICTY and the ICTR, as well as in the Preamble to the Rome Statute: to deter the recurrence of international crimes, and to hold the persons responsible for these crimes as accountable. Allowing for a dialogue on the difficulties faced by a global system is necessary to ensure that the international criminal justice process fulfills this goal, also referred to as the « fight against impunity ».

This aim is not as such questioned by the actors of international justice. Indeed, South Africa, in its letter of withdrawal, reiterated its commitment to justice and accountability. Similarly, even though the reasons of Burundi and Gambia for wanting to leave the ICC differed from those put forward by South Africa – they both referred to a policy of the ICC they deemed « racist », the two countries still did not imply that impunity should prevail over accountability for international crimes.

The challenges to be discussed pertain rather to the way the goal is achieved, i.e., for example, the application of the law on immunities, enhancing capacity building for national jurisdictions, reflecting on the role of the Security Council in the referral process to the ICC, or reinforcing complementarity. It is suggested here that similarly, issues pertaining to principles such as the presumption of innocence (from which fair trial rights and more generally the rights of the Defence ensue from) must be part of the dialogue. Indeed, the fight against impunity cannot be achieved if all parties involved do not seriously think that the court is able to fulfill both its repressive and protective functions.

President de Gurmendy and panel

From a system to a culture of international justice

The way to construct this dialogue is manifold. The panel discussion organized by the WAYAMO Foundation added a significant stone to the edifice, as have different working groups and conferences that took place since South Africa’s announcement in October 2016. Not to mention the ASP taking place every year, where many decisions concerning the functioning and the policies of the ICC are made. In this respect, the will of the WAYAMO Foundation to collaborate with artist Bradley McCallum in presenting his project Weights and Measures : Portraits of Justice, is telling of the existing interest towards the different and unconventional ways to build a dialogue around the challenges faced by international justice. Beyond the culture of justice that is promoted by institutions such as the WAYAMO Foundation, is it possible to build a culture of dialogue about international justice, inclusive of all viewpoints and able to tackle difficulties and challenges ?

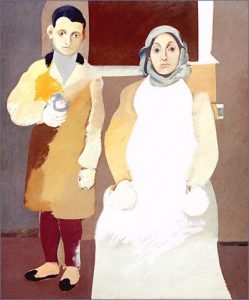

Weights and Measures : Portraits of Justice is a global art project by artist Bradley McCallum, dedicated to connecting people from different communities, through the universal language of portraiture. After four years of research, including a one-year residency with the Coalition for the International Criminal Court, the project evolved to encompass painted portraits of individuals standing trial for international crimes, photographic portraits of justice practitioners, and audio portraits of witnesses and survivors, thus giving a panoramic angle to the discussion as well as a physical space for it. The audio testimonial portraits, when paired with the photographs of the Justice Practitioners, will speak back to the persons in the paintings and suspend the viewer within the space of the dialogue. All the different stakeholders will therefore come together to discuss the challenges and achievements of international criminal justice.

Artist Bradley McCallum addressing the audience

The exhibition will tour in different countries. It will launch in March 2017 in Johannesburg, South Africa, and then travel to Kampala (Uganda), Nairobi (Kenya), and Goma (Democratic Republic of the Congo). It will reach its final destination, The Hague (The Netherlands), in October-November 2017. The presence of the exhibition in these locations will be marked by special dialogues on themes such as abuse of power, accountability, presumption of innocence, peace, and justice. In this way, Bradley McCallum seeks to create an atmosphere of intimacy and empathy and draw the participation of civic-based organizations and a broad general public. The goal of this dialogue is to allow the framework of how we understand the efforts towards accountability to be more global by including non-legal audiences, but also by creating a dialogue between the different parties to the system of international justice.

Creating Rights supports this project as it does not shy away from the difficult questions linking the practitioners of international justice together, as well as with the affected populations and the broader public: is a dialogue possible, and what do the forms it takes say about the culture of international justice being promoted ?

Bradley McCallum’s diptychs of individuals standing trial for international crimes, and audience

Credits to: Kris Kotarski/Wayamo