Children’s Drawings of the Genocide Against the Tutsi

Warning: this post contains sensitive photographs which some people may find disturbing.

The Shoah Memorial in Paris is hosting, from the 4th of April to the 17th of November, a commemorative exhibition of the genocide against the Tutsi, 25 years after it happened (as a small reminder, from April to mid-July 1994, almost a million ethnic Tutsi were massacred in Rwanda). I decided to go there. I misread the exhibit’s poster and thought that there was also a memorial for the Tutsi victims in addition to the memorial for the victims of the Holocaust. It turned out to be an exhibition only, but an instructive one.

As an international criminal law student, I am quite familiar with this, sadly famous, genocide and I was therefore expecting the exhibition to be emotionally heavy but even so, it hit me harder than expected.

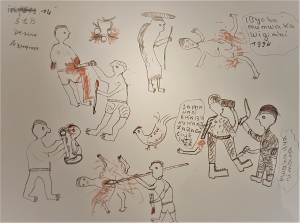

The commemoration is called “the genocide through the eyes of the child”. The organiser of the commemoration decided to exhibit the children’s drawings and stories. The first thing that really impacted me in this exhibition was the harshness and the violence in the children’s drawings. In the below drawing, by a 14 year old, one can clearly distinguish the blood drawn in red, as compared to the rest of the drawing which is black. The people being stabbed, people’s legs being cut, are visible to point out.

The notes made by the boy are even harder as they frankly explain what he experienced, “This is what happened to be during my teenage years in 1994 (up right); Here the interahamwe (a Hutu paramilitary organisation) cut my arm (center); This one is a military man from Habyarimana (down right)”

As Creating Rights had already been working on this subject (see for example Zérane Girardeau’s project Déflagrations) I had already seen children’s drawings and had already been shocked by the cruelty displayed in them. However, at the exhibition it felt different because there were a few people with me, reading the same stories, examining the same drawings. Some would sigh as they were confronted with the harshness of the testimonies. I have to say that when I arrived, I was quite in a good mood, but after reading only one story I directly felt touched and immersed in the terrible events that happened 25 years ago in Rwanda.

The second thing that impacted me was that the organiser did not only focus on the genocide itself but also on its consequences. This was, I think, very clever because, as it is a commemoration, 25 years after the events occurred, it is also interesting to examine what happened to the victims after the massacre. And, perhaps unsurprisingly, the situation did not improve. A victim even said, “life after the genocide was like a second genocide for the survivors and a third genocide for the orphans”. The exhibition gives the examples of women who, after being raped, eventually died of AIDS, half of the survivors who did not have a house; orphans who couldn’t go to orphanages because they were too crowded and who had troubles at school. A young girl testifies “people would say that survivor children were the stupid ones, but I would say we were intelligent because studying with all the problems that we have and manage to have the grades that we had, was a great sign of bravery”.

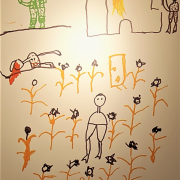

“The interahamwe came. They killed my neighbours and burned the house. I hid in a sorghum field.”