Young Liberian artists join the debate over accountability for war-time crimes

By Felix Lüth***

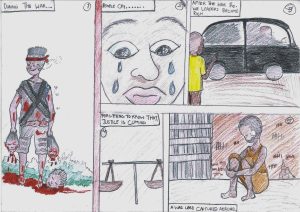

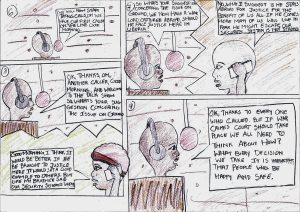

The movement demanding accountability for crimes committed during the two civil wars in Liberia was recently joined by a new and somewhat unusual group – young Liberian artists. So far, the debate (see previous blog posts here and here) had been carried by established justice advocates including prominent journalists, lawyers and other Liberian and international civil society members. But during a recent 4-day Cartooning for Justice Workshop, students from the Liberian Visual Arts Academy and other young artists started to raise their voices or rather their pens.

From 1989 to 1996 and 1999 to 2003, Liberia was beset by two civil wars which were notorious for their brutality and the widespread use of child soldiers. They not only resulted in the death of hundreds of thousands but also left many Liberians mutilated and traumatized. Today, 15 years after the end of the second civil war, still no one has been held accountable in Liberia.

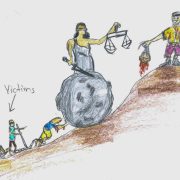

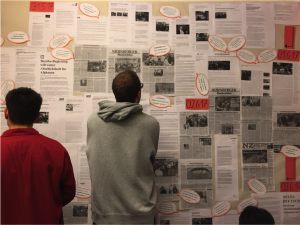

During the workshop, students learned storytelling and cartooning techniques and how they can use them to contribute to the ongoing accountability debate. After a brief introduction to the main philosophical approaches to the justification of punishment – often referred to as ‘theories of punishment’ – they were asked to find artistic responses through their cartoons to the question whether and why war-time crimes should be punished in Liberia today.

Cartoons? Comic strips? One may ask, what can they possibly contribute to such serious and complex questions?

The answer, I believe, is: Very much! Cartoons can exactly help with making complex issues more accessible both in terms of the message and reaching a broader audience.

A cartoon is a message being conveyed through a story in a sequence of drawings. When communicating a message mostly through images, we must simplify and focus on what is most important. However, when informed by in-depth research, in this case legal research on the theories of punishment and how they relate to the Liberian post-civil war context, a simple message does not have to be a simplistic one.

Cartoons cannot only make the message itself more accessible but also reach people who are not (yet) actively engaged in a public debate. This is particularly relevant in Liberia.

So far, the accountability debate has been led by senior civil society members from the capital, Monrovia. While this is of course quite normal, especially in a society like Liberia where much value is attached to respecting your elders, cartoons can help informing and engaging young Liberians who are not only many in numbers (over 63% of the Liberian population is under the age of 24) but also the future decision-makers of the country. In the same way, cartoons can help carry this important debate from Monrovia to the countryside where many of the most atrocious crimes were committed but people often have a harder time receiving and understanding written information.

In the words of one of the students: “Cartooning is also important because it gives those who don’t read and write the ability to know what is going on in Liberia and around the world.”

Finally, for many Liberians who have experienced the civil wars, it can be difficult to talk about it. Here, cartoons offer a less intimidating, more playful form of communication. In this sense, cartoons can also help bridging the generation gap between Liberians who have experienced the civil wars and those who have not.

The importance of cartoons and art in relation to debates on justice and accountability was widely confirmed by participants in the workshop, other members of society and the media.

Mae Azango, the award-winning Liberian journalist from FrontPage Africa, commented: “That [cartooning] is a very brilliant way to make the ordinary people like the market women, students, and many others understand the subject matter”.

“I think cartoons can help the situation of justice in Liberia by moving fear [from victim to perpetrator]” emphasised a student of the workshop.

“Combining art and justice is a way of igniting the flame for justice in Liberia” stated Hassan Bility, the director of the Global Justice and Research Project.

Cartoons can play an important role in promoting inclusive and informed debates on accountability for crimes committed during the civil wars in Liberia, in particular when informed by thorough research. But the contributions by young Liberian artists are not limited to cartoons: exciting theatre and music projects on issues of justice and accountability are on the way.

The workshop was organized by a group of different partners, including students from the Graduate Institute Geneva, the Geneva-based criminal justice NGO Civitas Maxima, its Monrovia-based sister organization Global Justice Research Project, and the independent Swiss-Congolese cartoonist, JP Kalonji, and sponsored by the Kathryn W. Davis Peace Foundation. A particularly important contribution was made by Livio Silva, Master student at the Graduate Institute Geneva, who managed the project and was part of the research team.

*** Felix Lüth is a Legal Counsel at Civitas Maxima, a PhD Candidate at the Graduate Institute Geneva and a Swiss National Science Foundation Research Fellow at King’s College London