“As long as my ballets are danced I will live”: 25 years after death, production about ballet genius Rudolf Nureyev not allowed to go ahead at Bolshoi

By Nolwenn Guibert*

On 8 July 2017, the General Director of the Bolshoi Theater, Vladimir Urin, cancelled, three days before its scheduled premiere, the production of a much anticipated new ballet about the life of former Soviet Union’s renowned artist, Rudolf Nureyev. Urin stated that he had cancelled the scheduled performances because rehearsals showed the production was not ready. For him, “the ballet was not good”. With a renowned choreographer, composer, a cast full of the leading stars of Moscow’s Bolshoi Ballet Company, one of the top ballet companies in the world, having worked on the project for months, this is hard to believe. A ballet staged for the Bolshoi and about to premiere is never simply “not good”. For people who attended the general rehearsal, the performance was ready to go ahead and was even in better shape than many other premieres.

In fact, soon after the news broke out, a Russian news agency, Tass, cited a source from the Ministry of Culture according to which the cancellation originated from pressure by Vladimir Medinsky, the Minister of Culture, because he was outraged by the ballet and feared it would be in contravention of the 2013 Russian law banning the promotion of homosexuality to minors (which would mean a hefty fine for the Bolshoi). The management of the Bolshoi Ballet and the Ministry of Culture have since denied that, although there had been a discussion between Urin and the Ministry, a government ban was not issued on the production.

As background, it is useful to recall that in 2013, Russia introduced a federal law which bans “the promoting of non-traditional sexual relationships among minors, expressed in the dissemination of information aimed at creating in minors a non-traditional sexual orientation, promoting the attractiveness of non-traditional sexual relationships, creating a distorted image of the social equivalence of traditional and non-traditional sexual relationships, or imposing information about non-traditional sexual relationships, arousing interest in such relationships, if these activities do not contain acts punishable under criminal law.” As a side note, just a few weeks ago, in a landmark six to one decision in the case of Bayev and Others v. Russia, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that the law violated Articles 10 and 14 of the European Convention on Human Rights (freedom of expression and prohibition of discrimination). The Court found that: “Above all, by adopting such laws the authorities reinforce stigma and prejudice and encourage homophobia, which is incompatible with the notions of equality, pluralism and tolerance inherent in a democratic society.”

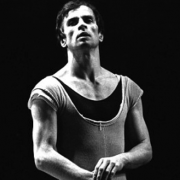

Known by all even outside the ballet world, Rudolf Nureyev was openly gay and was one of the first Soviet dancers to defect from the USSR in 1961. He, and the great artists who followed like Natalia Makarova, Mikhail Baryshnikov, and Alexander Godunov, to name a few, fled out of the Soviet Union in search of artistic freedom and to express their art free from censorship. At Le Bourget airport, near Paris, Nureyev delared: “I want to stay and be free”. Like all Soviet art, ballet in the Soviet Union was supposed to embody the principles of narodnost (nationality), ideinost (ideological content), and partiinost (party spirit), as explained in Christina Ezrahi’s book, Swans of the Kremlin: Ballet and Power in Soviet Russia.

In Paris, London, and New York, Nureyev went on to have as much of a profilic and acclaimed artistic career as a dancer, choreographer, and artistic director as he led a much talked about and scandalous personal life. In that sense, a true artistic depiction of Nureyev’s life would necessarily include some representation of his relationships and as such may very well have fallen under the scope of the 2013 law.

The Bolshoi production director, and Director of the Gogol Center for the Arts, Kirill Serebrennikov, made this sole comment on the performance’s cancellation: “While authorities and rules change, art is permanent.” Without Serebrennikov’s “Nureyev”, and until the 2013 law is repealed or there is a shift in the treatment of gay rights and freedom of expression in Russia, we are in any event left with the master’s many masterpieces. Incidentally, as this post is being written, Serebrennikov has been arrested in relation to a large fraud case and faces a maximum penalty of 10 years. The art world has been quick to react to this arrest and offer their support to Serebrennikov (see here and here), a man known for his talent and as an advocate of gay rights and a Putin opponent.

* The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Special Tribunal for Lebanon.