The Dream City is Tunis – part 1: The Maps of Dignity

The Dream City festival is a Tunisian art festival that takes place every two years since 2007. All the events are somehow politically engaged as the festival “addresses and deals with the social and political realities of Tunis in a fragile global context”, including among others migration, democracy, human rights, environmental crimes and memory. More than 50 events, ranging from concerts to conferences to exhibitions and movies, can be attended in the heart of the capital’s medina. This series of 2 posts will present some of this year’s events. This first post addresses The Maps of Dignity exhibition which examines how the notion of dignity is common to uprisings and revolutions in the Southern Mediterranean, from Morocco to Palestine, since the 1950s.

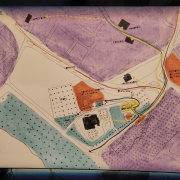

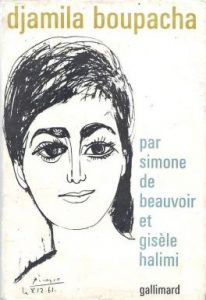

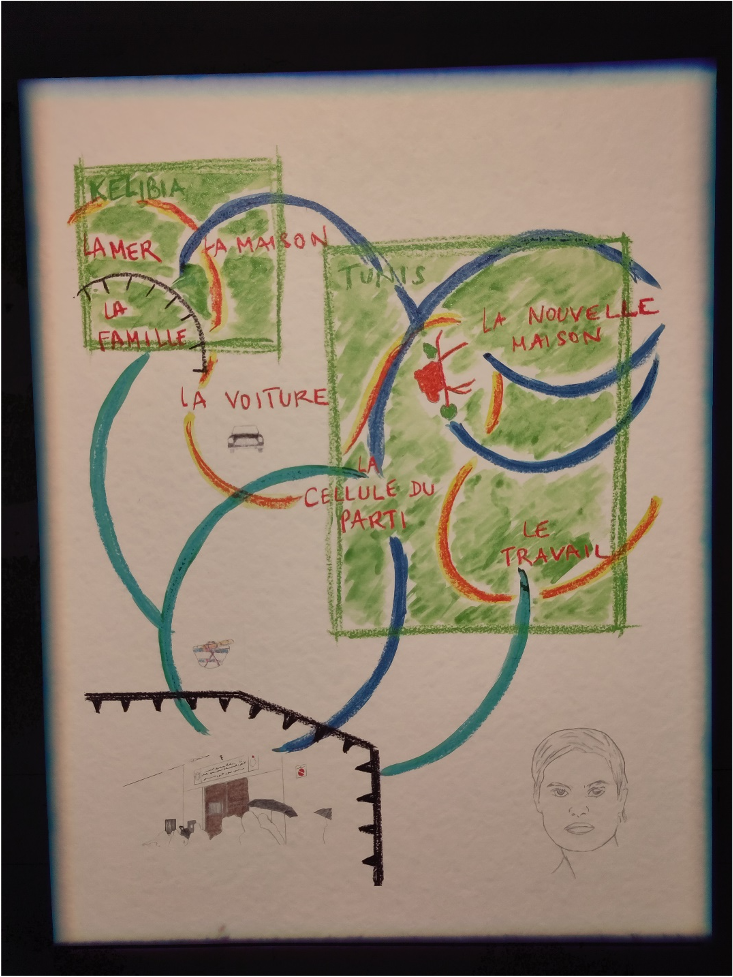

The first three maps of the exhibition explored the lives of women married to men imprisoned during the Habib Bourguiba regime. Although the former dictator who was toppled by the 2011 Tunisian Spring, Zine Ben Ali, has been erased from the capital, his predecessor Habib Bourguiba is still very much present. There’s the Bourguiba avenue, the Bourguiba language school, his statue on a horse, and taxi drivers never fail to mention his reforms when they tell me how Tunisians are more educated and open-minded than their neighbors. It was the first time – but I haven’t been in Tunis that long – that I saw public criticism of his regime. The maps represented where the women live (in green), where they feel free (red lines), where they are loving and loved (dark blue lines), helped and supported (light blue lines) and controlled (black lines). The prison is on the bottom left. A voice explained over speakers that one of them, Houria (freedom in Arabic), actually married her husband while he was in prison, and would smuggle messages outside as he would write on cigarette paper that he would then hide in his clothing which she would pick up for washing.

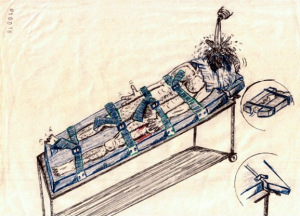

The Maps of Dignity also expose a very different type of map. At first, I thought it was a game to keep children occupied while their parents toured the beautiful Dar Ben Achour. Rather, the game is for adults who seek to get social housing. In this even more depressing version of the Monopoly, players start on square 1: handing in their form requesting social housing. As they throw the dice to advance towards finding decent accommodation, they are confronted with endless difficulties. For example, your kids grew up and got married? That sounds like great news, except because housing is too expensive, they come back home and you end up sleeping on the kitchen floor. Ironically, but probably sadly true, the rules state that the game never ends.

The maps exposed are at the same time geographical, artistic, mathematical and to some extent legal as some remind one of the compilations of maps and pictures of individuals in police investigations movies. I like the idea of using maps, but I might be biased: we love maps so much that me and my partner have four in our shared office. Even if I am biased however, I felt that the visual of these maps made the uprisings and human rights violations clearer. A map of Tunis during the 2011 Arab Spring showed how widespread the protests were. In Houria’s case, we can see how her husband’s imprisonment affected her whole life, from her house in Tunis all the way to her family in Kelibia. A map by an asylum seeker whose claim kept being denied for 10 years showed how a very accessible part of the city for me – where I hang out with friends, have a run and take a swim – was for him forbidden territory as he could only mostly stay in the dorms allocated to migrants (in yellow “where we were” and in purple “where others were”, while the orange part is “inaccessible”). A lady hosting the exhibition told me that these maps were a way to illustrate the research they did on the uprisings, and I think they succeeded.