Artistic exploration into international legal work: a matter of evidence?

by Fiana Gantheret

The question of the way different fields come together to enrich international criminal investigations and legal work was already touched upon here on Creating Rights when looking at Eyal Weizmann’s and Susan Schuppli’s project Forensic Architecture, a research project at the crossroads of international human rights law, architecture and engineering.

See You in The Hague by Stroom Den Haag, “a multifaceted narrative about the ambitions and reality of The Hague as international city of peace and justice”, offers further reflection on the encounter between artistic practice and international criminal processes, rendered here through the projects of Susan Schuppli and Jason File.

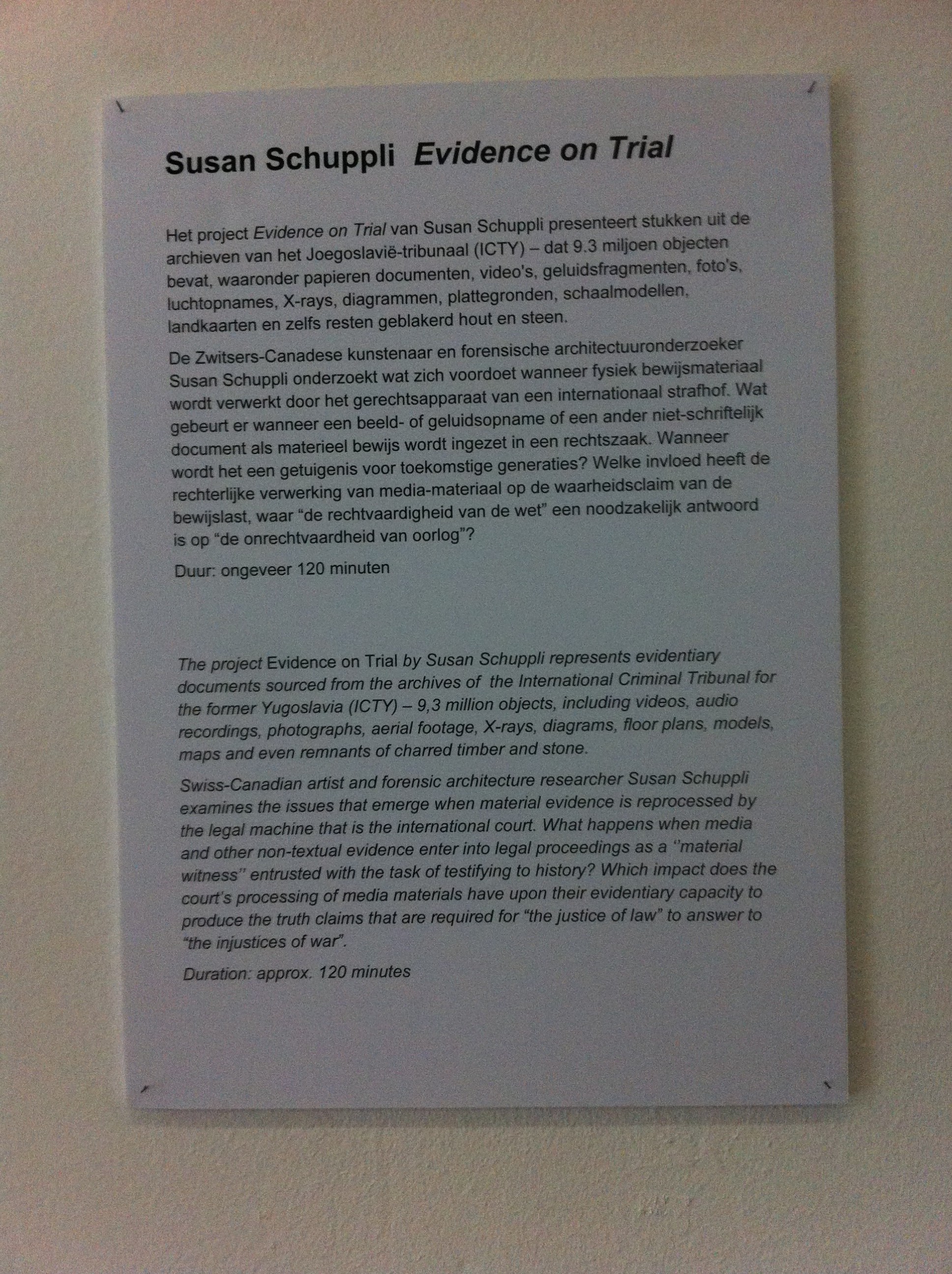

It presented last fall Susan Schuppli’s Evidence on Trial, a project featuring a conference and a video installation, as well as the screening of a documentary, Material Witness. Through these artistic manifestations, Susan Schuppli explores the path followed by media materials when presented in various public and legal forums such as international tribunals and agencies. What impact does court’s processings have on their evidentiary capacity to produce the truth, as required from them? Susan Schuppli’s project explores “how histories are materially and computationally encoded by media and by which means the complex political realities they are embedded in are rendered visible. In short, it is an inquiry into how objects become agents of contestation between different stake- holders and truth claims“. A methodology of a forensic nature in line with the one governing Forensic Architecture.

Evidence at Trial, Stroom Den Haag – 16 November 2016 Photographs by Fiana Gantheret

More recently, a duo exhibition was visible at Stroom Den Haag, entitled A Crushed Image (20 Years After Srebrenica), and presenting artwork by Jason File and Peter Koole. Peter Koole is a Dutch artist who, after having seen repeatedly the word Srebrenica on medias, decided for the first time to include it in his art work. Jason File is a contemporary visual artist, as well as a prosecutor at the United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. In the exhibition, Jason File presents various art works staging evidentiary documents in front of the international tribunal. As he explained himself during the finissage of the exhibition that took place in Stroom Den Haag on 12 April 2015, Jason File is interested in the ambiguity and subjectivity made possible through art, which legal work cannot offer. He uses evidence material such as autopsy drawings, hearings’ transcripts, and the day-to-day gesture of shredding confidential documents, and, by presenting them through artistic lenses, introduces ambiguity into legal work by interrogating their identities as objects.

A Crushed Image (20 Years After Srebrenica) – Jason File – The Earth and the Stars / Photographs by Fiana Gantheret

A Crushed Image (20 Years After Srebrenica) – Jason File – The End Photograph by Fiana Gantheret

Both Jason File and Susan Schuppli’s projects raise the following question: is it possible to think as artists in a domain that isn’t artistic? In other words, what to think about what art has to say and the relevance of it for international legal processes? As Jason File puts it in Post Script – a text written in an attempt to answer the question of whether it is possible for someone in the legal profession to have a double articulation that includes the making of art – “aesthetic critique is incompatible with properly-functioning judicial systems from the internal perspective of the operations of a trial”. Rather, if critique there is, it will follow an internal pattern of rules. Jason File explains this by referring to the mandate given to international criminal proceedings to establishing facts beyond a reasonable doubt and applying a normative judgment to them. He also refers to the underlying assumption that there is an objective truth that the international criminal justice system tends to ascertain, to a degree that allows confidence in the system’s ability to do “justice”.

He therefore describes a criterion, presiding over the choices made in determining which sets of rules will define the field in question. In Justice, Uncompressed, published along with the exhibition, Jason File compares these choices to those driving digital image compression:

In its laws, rules, procedures, technology and practical resource constraints, an international criminal tribunal has its own compression algorithm. Under a tent, the physical remains of a victim excavated from a mass grave are converted into words and images on paper through the mediating influence of an investigator drafting a report. The report becomes a proxy for the real thing, the smell of the location, the dirt, the feel of a bone which itself stands in for the personal experience of the victim itself, now irretrievably lost. Much raw information and experience is removed in order to distill the facts that are relevant for the purpose of the investigation.

The question of the confrontation between the fields of justice and art was at the core of the debate that ended Susan Schuppli’s Evidence on Trial, and which took place on 16 November 2014 in The Hague Institute for Global Justice. There, Susan Schuppli’s text Entering Evidence, in which she “conceptually interrogate(s) the ways in which the post-production treatment of media materials – their copying, editing, digitalizing, and chain-of-custody handling – impacts upon their evidentiary capacity to produce the truth claims that are required for ‘the justice of law’ to answer the ‘injustices of war’”, was discussed by practitioners of international criminal justice. They made the remark, in particular, that “the research of media materials in the ICTY archives should be left strictly to legal professionals” (for a thorough account of the debate following the conference, as well as interesting thoughts on the relationship between arts, peace and justice, see Brigitte van der Sande’s post on See you in The Hague Blog).

Jason File and Susan Schuppli concur to think that there should be more opportunities to communicate between both worlds, which would each benefit from such collaboration. From the internal perspective of international criminal processes, forensic work such as the one performed by Susan Schuppli could bring a meaningful contribution by interrogating evidence material, provided that the conditions of admissibility and evaluation of evidence be respected, namely in accord with the “internal pattern of rules”. Even if Susan Schuppli’s approach has an artistic aim that is external to its object of study – international criminal operations – it can be made compatible to a judicial evaluation of the evidence from an internal point of view and therefore contribute to the judicial truth, the “objective truth”, as described by Jason File in Post-Script. On the other hand, one must distinguish between the judicial truth as produced by international tribunals and a broader artistic approach which, as in the case of Jason File’s work, takes part in a collective and socio-philosophical vision not focusing on individual criminal responsibility. In the latter case, the object of study is extracted form its context and submitted to an artistic and external understanding. In this instance, there is, in our view, no other relation between the two fields than one of mutual respect and interest.