Artistic and legal objects: Abu Zubaydah’s drawings depicting detention at Guantanamo

Warning: this post contains sensitive drawings which some people may find disturbing.

What is art? Is Abu Zubaydah’s drawings of the torture methods used against him “art”?

As explained in an article published in the newspaper The New York Times on December 4, 2019, Abu Zubaydah is a Saudi national who was arrested in Pakistan in 2002 by the USA suspected of being an Al Qaeda member. He spent 4 years in the CIA secret prisons before being transferred to Guantanamo bay in 2006, where he is still being held today. Allegedly, he is the first person to have been subjected to the CIA’s torture interrogation programme. This programme was created by two CIA psychologists and approved by no one else then the USA President at the time, George W. Bush.

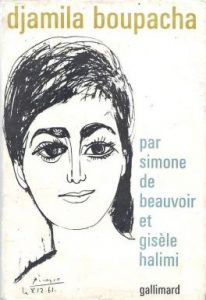

Last December, his lawyer Mark Denbeaux released a report entitled “How America Tortures”. In this report, Denbeaux points out that “Americans may find it difficult to acknowledge that top officials […] orchestrated and poorly oversaw a terrific torture programme”. He therefore suggests telling the American people, and anyone reading this report about the crimes committed by the CIA in Guantanamo, and hopefully to raise awareness. A series of Zubaydah’s drawings portraying the torture techniques he was subjected to are included in the report. They were first published in 2018, on Propublica.

Referring to my earlier question: are these torture drawings art?

For the Cambridge dictionary, yes. Art is defined as “painting, drawing, sculpture, etc.” As for the literal meaning, Abu Zubaydah’s are therefore art. The Guantanamo penitentiary administration and the USA military seem to disagree. Indeed, even if the Guantanamo prisons offer “art” classes to captives, students are not allowed to artistically represent their life at the Guantanamo bay. Detainees can only draw and paint still life or do Arabic calligraphy. In addition, detainees used to be able to send their art works, such as drawings, paintings or even small boat constructions, to their relatives. The penitentiary administration would inspect it to make sure there would be no secret messages, but if that wasn’t the case, the artworks would be shipped to the inmates’ family members. However, since 2017 the USA military has decided that art pieces made by the detainees were no longer considered to be their property. Due to this decision, Zubaydah’s lawyer released his client’s drawings as “’legal material” rather than art, making the publication of those sketches possible.

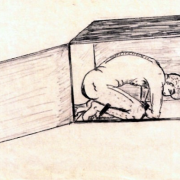

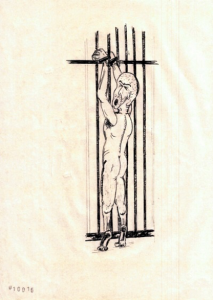

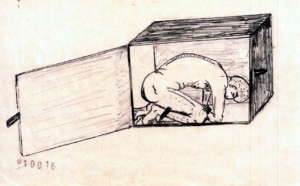

As to whether Abu Zubaydah’s drawings are called “legal materials” or “art”, there is, in my opinion, no doubt his sketches are actual art. Granted, they are dark, depressing and terrifying pieces, but art nevertheless and consider Zubaydah to be quite gifted. Take for example the image below in which he represents one of the torture techniques: walling. As one can see in the drawing thanks to the red lines, walling is to bang the detainee’s head on the wall several times a day. No details are speared as the artist shows his scars on his left thigh, on his skull and on his chest, shows the suffering (his eyes are closed and his mouth seems to be screaming in pain), the nudity and the shackles which seem very uncomfortable as they oblige him to always have his hands stretched in front of his body.

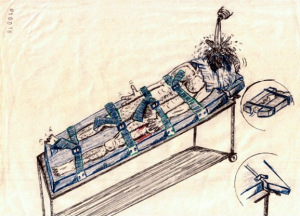

Another example is the waterboarding drawing in which we can feel the pain of the inmate and learn a lot about the actual waterboarding technique. Indeed, the way Zubaydah portrays his right foot, right hand and head as shaking because of the pain and the blood coming out of his left leg makes the viewer feel actual chills when closely looking at the drawing. In addition, the terrible sketch shows us how the board would be lowered at the head’s level so that it would be closer to the ground than the rest of the body. This is done to make sure the water doesn’t actually go in the victim’s airways but still imitates the sensation of drowning.

Beyond theoretical considerations concerning the nature of Zubaydah’s drawings, they show an underlying story about torture techniques being used by the CIA in Guantanamo bay.

Recently, an American military commission investigating the role of five persons accused of having participated in the 9/11 terror attack heard the testimonies of the two psychologistswho had been in charged of designed the torture programme. The pre-trial however, revolves around 9/11 rather than Guantanamo or CIA black sites. The torture suffered by Abu Zubaydah and other inmates has therefore not been punished yet, and it seems important to continue raising awareness about those inhumane methods.