Picasso and the War

When I think of Picasso, I think of weird shaped and coloured women. Of course, I think of Guernica too but that only comes later, and little did I know of the artist’s actual political commitment. Therefore, when answering the Musée de l’Armée’s survey, I check the box “totally agree” to the question “Did you learn something during this exhibition?”

The exhibition I am referring to is the Picasso et la guerre (Picasso and the war) exhibition in the Army’s Museum in Paris which will be open to the public until the 28th of July 2019.

The exhibition guides you through Picasso’s evolution of how he perceived and painted war. The first drawings are from when he is 11 or 14 years old. They are the typical drawings of a child, a very talented one, who likes drawing war scenes with soldiers and horses. It doesn’t seem that there is a deeper meaning to them. The First World War did not affect Picasso even if he is at the centre of it, in France, at that time.

A turning point for him was the Spanish civil war and, of course, Guernica. Picasso’s painting of Guernica will become one of the most famous anti-war artwork and will mark the beginning of Picasso’s political commitment. Sadly, Guernica was not at the exhibition as it is in Madrid’s Reina Sofía Museum. I knew Picasso had painted Guernica and I was familiar with his opposition to the Franco regime. What I failed to know was that he was also very active in raising awareness about other conflicts.

After World War II, he joined the French communist party and started being more active on the political scene, vocally and also artistically.

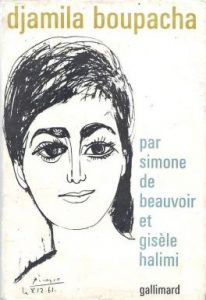

His main focus was to paint portraits for newspaper articles, books or commemoration booklets. For example, he drew the portrait of an unknown man for a commemoration event at the Auschwitz concentration camp and the portrait of Djamila Boupacha for the cover of Gisèle Halimi and Simone de Beauvoir’s book about her. Djamila Boupacha was a FNL (Algerian National Liberation Front) activist who, after attempting to bomb a café in Algiers was arrested by the French army, tortured and raped. Her trial became a political trial in which her lawyer, the feminist Gisèle Halimi, condemned the violent methods of the French army during the Algerian independence war.

One of the key artwork of the exhibition is the Massacre of Korea. Again, I had no idea Picasso had been actively campaigning against the Korean war. The cubist, surrealist painting portrays the No Gun Ri massacre in which 250 to 300 South Korean refugees (women and children) were killed by the American army. With this painting, Picasso seems to be opposing American imperialism but also the Cold War, and war in general.

Last but not least, Picasso is said by some to be the one who popularized the white dove as a peace symbol. He was not the inventor of this symbol as the dove was present, for example, in the Bible but he made it popular and secularized it when he drew it in 1949 for the World Peace Council in Paris. The dove was used again for the 1950 and 1952 World Peace Congress and since then became one of the main icon representing world peace.

Dove of Peace

What the exhibition seems to forget however is that Picasso also did the portrait of Joseph Stalin for the communist newspaper Les lettres françaises (the French letters) just after the USSR leader died. The front page of the paper stated “What we owe to Stalin?”. I am not a Picasso expert and therefore don’t know what his opinion was of the soviet leader. However, it does bother me that “the Artist for Peace,” as the exhibition calls him, would draw the portrait of a man who killed millions of people.